Where the Study got it Wrong: A Lack of Valuable Contribution to Bitcoin Economics and a use of Flawed Economics in General

This study, while undoubtedly conducting fascinating research with a lot of useful, historical data, got two major things wrong; the first thing is that it did not add anything of value to the discussion of Bitcoin economic theory; people in the community have known about the connection between search trends and changes in the Bitcoin price for some time. The second thing the study did wrong was that it used extremely flawed economics. The study relied almost solely upon quantitative analysis, while mistakenly falling into the trap of historicism and the fallacious cost-of-production theory of value.

The first thing we will discuss is how the study failed to contribute anything of value to Bitcoin economics, since it is the most obvious of the two mistakes made by the researchers. The thesis of the paper alone indicates as much; the entire argument of the paper was that increases in “social signals,” ie. Internet searches and social media sharing, led to an increase in Bitcoin price. The fact of the matter is that the Bitcoin community has been aware of this connection for a very long time.

When searching the term “Google trends” on /r/Bitcoin, the main Bitcoin forum on Reddit, the earliest mention of Google trends, seen by this author, dated back 3 years. The post was a humorous indication that the social popularity of Bitcoin was on the rise, pointing out to subreddit members that “bitcoin” had surpassed “anal fisting” in search volume on Google.

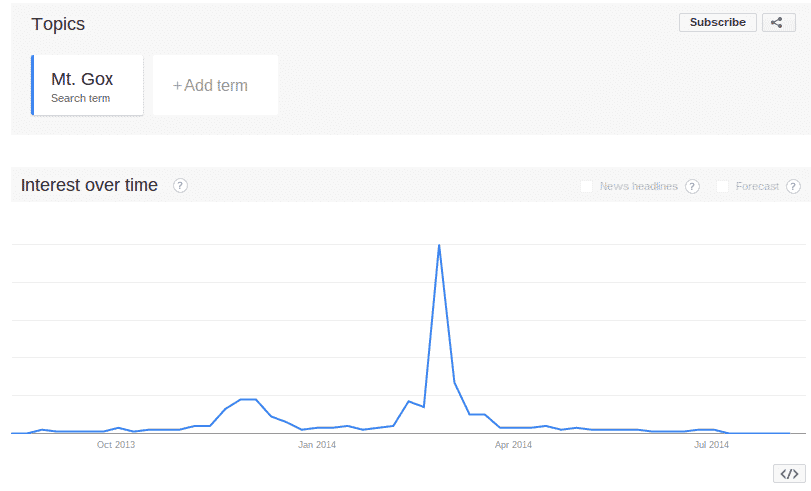

In a much more serious post, from 2 years ago, the original poster superimposed the Google search trend line for “bitcoin” over the Mt. Gox USD chart for the Bitcoin price. And that post is not the only one directly comparing Google trends to the Bitcoin price; several threads that date back anywhere from 1 month to 1 year bring up Google trends and either asked the community if there was any link between increased searches and prices or predicted an increase in the Bitcoin price as a result of search increases.

Furthermore, when searching for the term “Google trends” on /r/bitcoinmarkets, a Bitcoin subreddit dedicated to speculative discussion about prices, which often turns towards Bitcoin price analysis for answers, we receive similar results to those gained when we searched for the term on /r/Bitcoin. In posts going back several months, some even as far back as a year, people compared Google searches for bitcoin to movements in the price and also speculated on movements in the price based on changes in the search trends.

So, the Bitcoin community on Reddit has been paying attention to Google trends for at least three years; we might have even found posts farther back if we had dug a little deeper. Despite the web of quantitative analysis and technical jargon, the Swiss researchers essentially did the same thing that the Bitcoin community has been doing for a very long time, superimposing graphs upon each other. Therefore, the fact that the Swiss study’s “discovery” of a connection between social awareness of Bitcoin and its price was not really a discovery at all, thereby adding nothing of value to economic discussions going on in the Bitcoin community, should be enough to discredit the paper entirely.

But, in order to further prove how inadequate research led to incomplete conclusions in the study, we will look at how the researchers did an unsatisfactory job at explaining how social awareness causes both increases and decreases in the Bitcoin price.

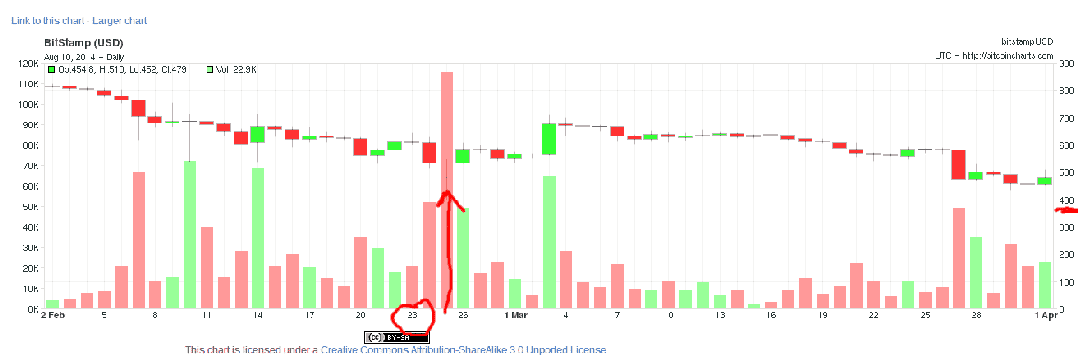

The researchers’ use of search trends and WOM sharing is a viable way to look for a correlation between changes in social awareness and changes in the Bitcoin price is a viable research method. However, they limited themselves to only one term, which was “bitcoin.” This led them to the conclusion that increases in social awareness led both to increases and decreases in the price. Although that conclusion is somewhat true, the study does not do a satisfactory job explaining why that is so. For they failed to address the qualitative differences between the different waves of social awareness; they neglected the fact that social awareness carries both positive and negative connotations. While the researchers did concede that the major crashes were largely due to negative happenings in the community, such as the Mt. Gox attack, they treated those events as “external” influences on the Bitcoin price, separate from the growing volume in Googling and WOM sharing. Why do negative events have to be externalities? They are just as much market activities as are searching “bitcoin” on the Internet and tweeting about it to your friends. When we treat both positive and negative events as equal, internal components of the market, it becomes obvious that an increase in social awareness can cause both positive and negative movements in the Bitcoin price. For example, if we expand upon the study’s Internet searching dataset and look at how searches for “Mt. Gox” correlates with the Bitcoin price, then we can see a perfect example of how social awareness can cause a decrease in the price.

When we search “Mt. Gox” in Google trends, we see a huge spike in the search volume at the end February and the beginning of March in 2014. This time is when the Mt. Gox Bitcoin exchange shut down. At the same time, there was a similar spike in sell volume on the Bitstamp Bitcoin exchange, with a corresponding fall in the price from around $550 to $400. As we can see, if we broaden the search terms just a small bit, so that more of the Bitcoin economy is included, it is extremely clear that increased social awareness is not always positive. Those negative influences on the Bitcoin price cannot be considered externalities, because there are no such things when we are considering such a broad swath of economic activity. The Bitcoin economy is exactly that, an entire economy; but it seems as if the researchers in this study preferred to treat the Bitcoin economy as a single firm, thus eliciting a faulty analysis of bitcoin’s price.

In conclusion, while the researchers were essentially right in their statement that peak social awareness has historically been followed by a sharp fall in the Bitcoin price, they failed to adequately explain why such price drops happened. They identified the correct sources of price drops, but incorrectly dismissed them as external influences so that they would not impede the study.

However, the researchers also made a few, glaring mistakes in their choice of economic theories and methodologies. These mistakes warrant further discussion, as a correct understanding of economics is essential in coming to a thorough understanding of Bitcoin. Let us turn to the research team’s fallacious use of the cost-of-production theory of value, in determining the “fundamental” value of one bitcoin, and their use of historicism, an untenable, anti-economics doctrine.

The Cost-of-Production Theory of Value as the Study Related it to Bitcoin Value

The team claimed that, in order to set a lower bound for Bitcoin value that they could use as some type of baseline or control, they needed to find the fundamental value of a single bitcoin. To find this, so-called, fundamental value, they employed some mathematics and figured out the approximate cost of production for one bitcoin.

The problem with this method is twofold. On the one hand, it used the antiquated and long-disproven cost-of-production theory of value. This theory states that the value of an object comes from the value of the resources required to produce it. On the other hand, a fundamental Bitcoin value simply cannot exist and is unnecessary for any type of study into the Bitcoin price. However, the latter problem involved with the overall flaw in this particular research methodology is merely an offshoot of the fallacious cost-of-production theory of value. Therefore, we will first explain the uselessness of this theory—then, the absurdity of finding a fundamental Bitcoin value will become obvious.

The cost-of-production theory of value, as mentioned above, states that the value of a good derives from the cost of the production factors that are used in making the good. This theory is simply untenable, though, because it falls victim to the mistake of looking at the science of economics through the eyes of a single firm. Of course, to a single Bitcoin miner, the costs of running his rig would be the sole decider of whether or not he would continue mining. But that does not mean, however, that we can use the costs of production as a baseline measure of value. Even though it may seem this way to the miner, the costs of production are not the ultimate given of the production structure and cannot be considered a constant.

In reality, the production structure traces all the way back to the valuations of individuals—for nothing else really could determine the value of producer’s goods. The value of the productive factors comes from the value of the consumer’s goods that those factors produce, which are themselves valuated by the subjective magnitudes of satisfaction that individuals receive from consuming the goods. So, while the miner may think that the value of the electricity that produces his bitcoins will always be constant, it is continuously fluctuating from changes in the subjective valuations of people who are using electricity for other purposes. Thus, the price of electricity could suddenly plunge or skyrocket, consequently increasing or decreasing the cost of bitcoin mining. The fact that the price of electricity remained relatively stable during the time period considered in the Swiss study is merely a historical datum, it cannot be treated as an economic given, as part of a cost-of-production theory of value.

This truth leads us to the researchers’ statement that calculating a fundamental Bitcoin value would allow them to set up a baseline measurement of Bitcoin value without relying upon the subjective valuations of individuals. Given our refutation of the cost-of-production theory of value, we already understand the absurdity of such a statement. The simple fact that the costs of Bitcoin mining are actually determined by subjective valuations invalidates the entire concept of a fundamental Bitcoin value that is independent of subjective valuation.

Although, it could be argued that the broader, theoretical implications of the pricing process of the factors of production do not apply to the Swiss study, for they actually are determining the fundamental value of a bitcoin from the perspective of an individual miner. But even then, they are still using a value that is both determined by subjective valuations and is never perfectly constant, making it unfit for use as a baseline measurement. Additionally, using the mining costs of Bitcoin as a constant, baseline measurement of value is fallacious because the costs of Bitcoin mining are constantly increasing, even if the value of the productive factors remains the same. The reason for this ever-rising mining cost is that Bitcoin mining gets more and more difficult as more coins are mined, requiring a greater expenditure of resources.

So if the fundamental value of one bitcoin is measured by its production costs, then that value could never be constant, since the costs of Bitcoin mining are always rising. Thus, when the researchers “discovered” that the actual Bitcoin price never fell below the fundamental value, they once again failed to add anything of value to the current knowledge about Bitcoin. For Bitcoin mining will not continue if the revenue provided from mining ceases to cover the costs of production, this mechanism is hard-coded into the Bitcoin protocol. Bitcoin is deflationary by design, so of course mining will not continue if costs exceed revenue! In conclusion, there can never be a measure of Bitcoin value that can serve as a constant or a control, for all value is determined by the ever-changing valuations of individuals.

Besides, even if there was such a thing as a fundamental Bitcoin value, then why would the miners even care about the monetary price of a bitcoin? If the Bitcoin price fell below the fundamental value, would the miners not continue producing bitcoins simply for the fundamental value they provide? The very idea of a fundamental value is untenable because it is, in fact, self-contradictory. If the costs of production produce value, then it will always be worth it to continue production—regardless of revenue or profit—because value will be created as long as production remains ongoing. Even if no one will buy the product that is made, it will still have value because of the costs that were involved in making it. Therefore, if a fundamental Bitcoin value existed, miners would always be able to sell their bitcoins, even if no one was buying them! The absurdity of the idea of a fundamental, unchanging Bitcoin value is painfully clear.

Continued on Page 3

No Comments

No Comments